As we know, quality whisky takes years to make, costs more to buy, and is rarely consumed without intent. The reality, like it or not, is that it was never meant to behave like a “typical” fast-moving consumer good. Yet much of the industry still borrows its growth language from categories built on repetition.

Premium whisky sales are low frequency by design, but it feels like that’s sometimes forgotten.

This mismatch opens the door to a conversation that looks like a business version of ping pong as the same ideas are batted back and forth. In many ways, the game is set up to fail because when a product sales cycle is structurally low frequency, the wrong metrics and expectations distort decision-making. Classic conversations around loyalty programmes, cadence-based engagement, and short-term volume targets assume regular replenishment. But premium whisky doesn’t replenish that way, and neither do its buyers. So why are we surprised?

Price of patience

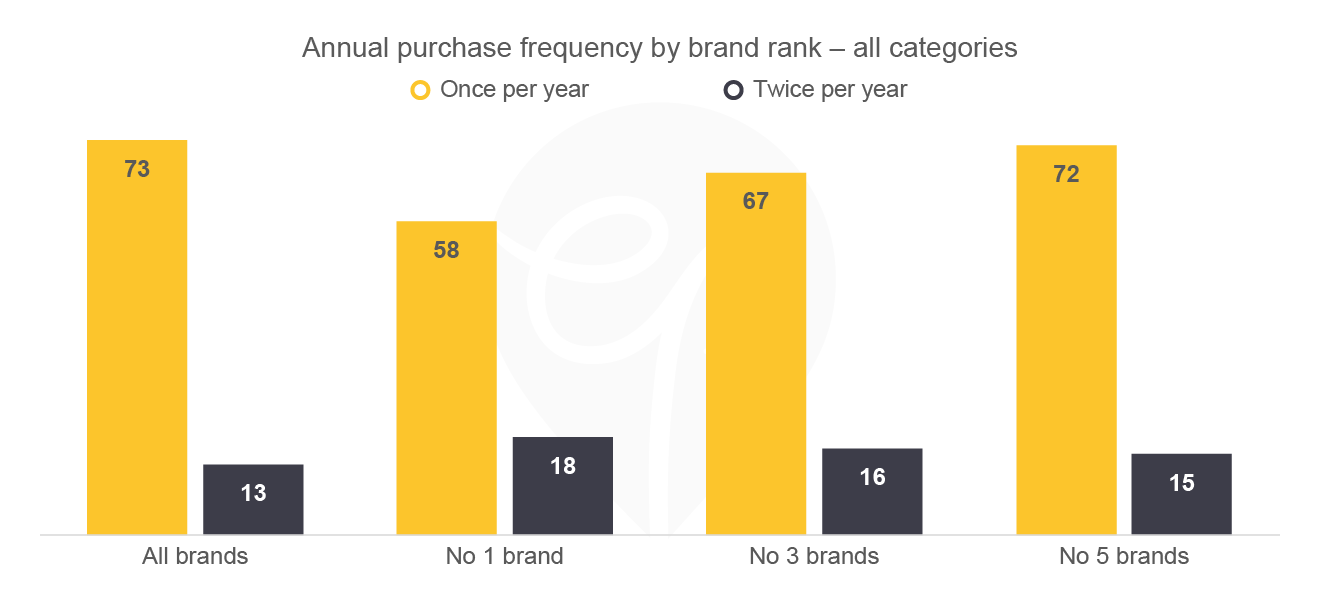

The latest consumer data from Europanel puts this into sharp relief across European FMCG markets. Three out of four brand buyers purchase only once a year, even for the biggest brands. Market leaders still see 58% of their buyers make a single annual purchase, rising to 72% for smaller brands.

Pushing the numbers further, in frequently purchased categories, one-time buyers fall to around four in ten. In infrequently purchased categories, they rise to two-thirds or more. So what I’m saying is this: light buying isn’t a failure of brand performance; it’s inevitable, a structural outcome of how often people buy.

Whisky is almost the poster child for this kind of behaviour. In a low-frequency, high-price category, the pool of non-buyers is vast, the pool of one-time buyers is large, and the pool of regular buyers is small by definition. Trying to squeeze more from existing customers in that context risks fighting the physics of the category. Growth comes from reaching more people, not squeezing more from existing customers.

People power

This is where the challenge for whisky becomes explicit. If most buyers purchase once a year or less, growth can’t depend solely on tightening the relationship loop. No matter how many times the “equals” button is pushed on the boardroom calculators, it won’t compute. Because it can’t.

So, what to do during these inevitably long periods of buying silence? We first need to recognise the real competitive set isn’t other whiskies; it’s everything else that might fill that rare buying moment, including wine, non-alcoholic alternatives, luxury goods, or nothing at all.

Growth comes from being the obvious choice at the point of decision. If we can’t sell more whisky to the same people, we must find more people and recruit them to the category.

That brings an accessibility problem to the front of the room. Drinkers, young and old, have long described whisky as a tough choice compared to other brown and white spirits. It feels daunting, has a reputation for being expensive, and is a drink they struggle to see themselves as part of.

New views

That reframes the strategic task. The question stops being how to make people buy whisky more often and becomes how to remain the obvious choice when they do decide to buy. That’s a different discipline, and one that (importantly) privileges clarity over complexity.

It also explains why premiumisation has been both a strength and a constraint. Trading up works well in low-frequency categories because each purchase carries weight. But it also narrows the margin for error. When people buy less often, they tolerate less confusion, less friction, and less justification. The bottle (or dram, or cocktail) has to earn its place quickly.

The industry often treats light buyers as a conversion problem. I’d argue the data suggests they are the category, and that in a business built on patience, the one-time buyer isn’t so much a failure of loyalty as the economic baseline.

As the saying goes, hope isn’t a strategy. A new conversation is needed because the pressures facing whisky now all compound low-frequency behaviours. Moderation trends reduce occasions. Cost pressures lengthen replacement cycles. Tariffs and pricing shifts raise the stakes of each decision. None of these forces argues for chasing frequency. It would be madness to expect that to be successful.

Premium whisky already understands scarcity in production, but the next phase is likely to be understanding it in demand. The brands that adapt will stop fighting the nature of the category and organise around it.

This piece was also published on LinkedIn.